You can't make it normal. That's the most glorious thing about it. In whatever light, at whatever time, it still looks irreducibly hopelessly strange.

The BT Tower is just a little bit too weird to ever settle into its environment. There's something otherworldly about its shape - thick glass base, thin collar, bulbed top - that doesn't immediately fit into any of our pre-existing visual categories. You sort of dimly think that it should look comically phallic, but it doesn't. It looks old, but futuristic. Dated, but modern. Pedestrian, but bizarre. It's impossibly tall, but it is oddly intimate. It is corporate, but it is not characterless. It has a genuine eccentricity that emerges from its form and function rather than the try-hard fake bonhomie of financial monstrosities like the Walkie Talkie or the Cheese Grater.

The news this week that they are going to sell the BT Tower to a hotel group honestly doesn't matter. They can do whatever they like with the internals. It's the externals that matter.

That speaks to its beauty. Most skyscrapers are stone-faced empty things. They're expressions of an insecure wannabe virility, designed to prove the stature of a city rather than from any real sense of need. They're the product of the rich, by the rich, for the rich, and therefore more concerned with the view of the person at the top than the person at the bottom. They prize the luxury of the man on the inside, rather than the urban environment of the guy on the outside. The BT Tower is the opposite. The view of it from the ground-up is more important than the one from the sky-down. Why? Because a view over London is not unusual. You can get it on the London Eye, or Centre Point, or from the top of Parliament Hill. But the BT Tower is very unusual, and the sight of it is therefore more of a privilege.

If there was anything heartening about the news it was simply that the building would have a purpose now that BT is done with it, even if it's only to house an expensive hotel. That matters. Beauty is more profound when it has utility. Look at the red phone boxes. They're still lovely to look at, but they've turned into an expression of national sentimentality. Their true value lay in a society that wanted to make everyday functional objects handsome. The moment the function goes, as it has done for them, they become flamboyant and nostalgic - show-off remnants of a more elegant age.

When you live in the city, you in fact inhabit three realities. The first is the day-to-day reality of the place - the pubs you go to, the buses you take, the route home from work. The second is the city as you conceived it before you arrived - the things you knew of it before, the mythical form of it in your imagination, which is overlaid on the practical form you know now. And the third is the city you used to know, as it changes and fades around you, becoming lost to the new.

The London I arrived in when I turned 18 was composed primarily of St Pauls and the BT Tower. Big Ben never really figured into it. It was too obvious, like a dead metaphor. But St Pauls and the BT Tower were in the comics I'd grown up with.

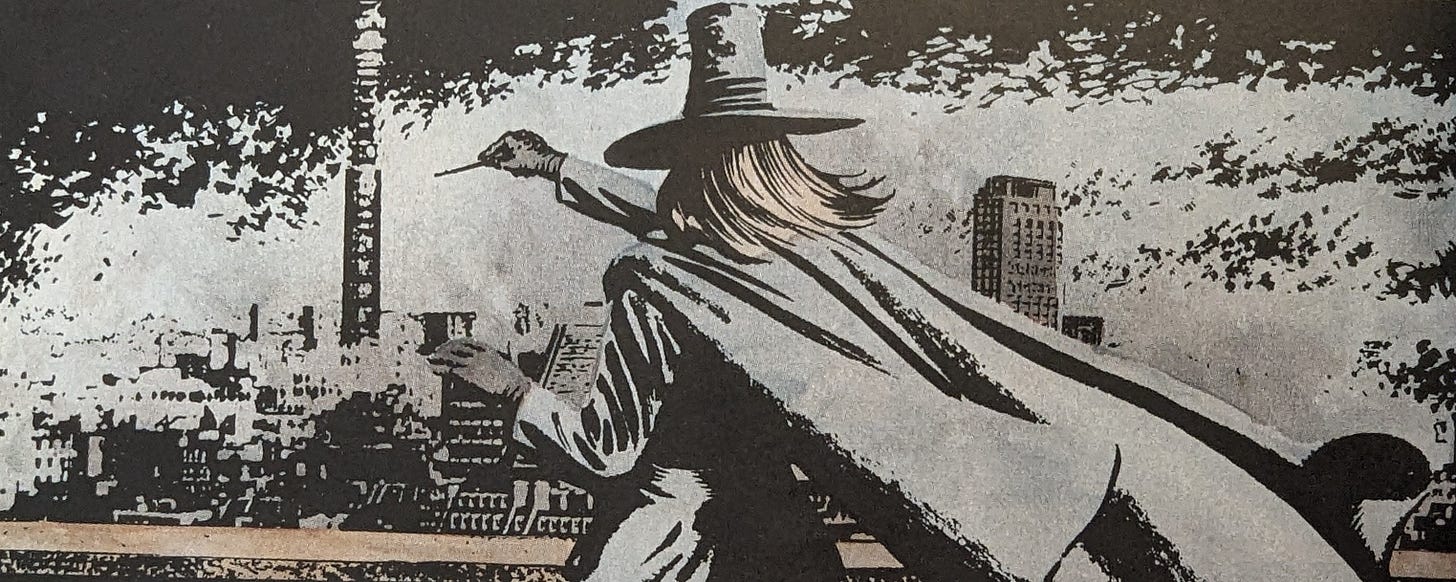

St Pauls was always in the background when John Constantine walked around in the rain, lighting a cigarette and pulling his raincoat around him. The BT Tower was the 'Ears' function in Alan Moore And David Lloyd's V For Vendetta - the surveillance hub for the drab futurism of their fascist London. They became part of my mental architecture of the city. And what a perfect combination to summarise London: the old and the new, a city with one foot in the past and the other striding forward. A place that, even when it aspires to modernity, always feels blooded by history.

Outside of the Boot and Flogger, by London Bridge, you can stand and look at the Cross Bones, an unconsecrated cemetery where they buried 'Winchester Geese' - sex workers - in the post-medieval period. When they tried to excavate the ground during construction of the Jubilee Line they found the bodies piled up, one on top of the other, in their thousands. Today, people still leave messages to the people who died there. They write little notes on ribbons to women who lived over half a millennium ago, and attach them to the gate. And above it all stands the Shard, vast and indifferent. And in that view - of the cemetery, the notes, and the skyscraper - you get a sense of what London is and will always be. Somewhere that always feels slightly haunted.

When I first arrived in the city, I lived in student halls in the shadow of the BT Tower. It was the only year of my life that I lived in central London and it functioned effectively as a homing beacon. Those first few months you start to pace out the city, simultaneously surprised by how small and how large it is. The various locations in the centre, like Chinatown and Trafalgar Square, seem so different, but they're in fact very compact and easy to reach on foot. And yet the tributaries and the smaller streets are endless and chaotic, a jumbled mess of counter-intuitive routes and pathways that go nowhere. You could spend your life trying to walk them all and you would fail. They branch out from every road, stretching right into outer London. The city would shrink and bulge as you explored it. And yet you always knew where home was, because of the tower.

I remember taking magic mushrooms once, on a muggy summer's day, and basically half losing my mind as it turned into night - just overdoing it a bit and suddenly having to deal with the weird contorted faces staring out at me from the street. I was at that point where you're not entirely sure who or where or when you are. But I saw the BT Tower and I knew: OK, I can follow that home.

The older you get, the more transitory buildings feel. I did a talk at my old school recently. I tried to walk into the Sixth Form concourse when I realised that it did not exist. Or rather, the building had been restructured, walls knocked down and moved, stairs shifted along, until nothing was recognisable anymore. All those memories of that place now existed only as memories, not as imprints in a contained physical space.

The same happens to you in cities, although it happens much more aggressively, especially in a place like London, that is always grasping for change, furiously switching up to whatever will make money next. The shops change, the people change, the buildings are knocked down. The first office where I worked as a journalist no longer exists. One of the places where I used to get a late night kebab is now selling tubs of frozen yoghurt, which for some inexplicable reason is now considered the solution to all the world's problems.

Cities age you faster than towns or villages, because they shift around you with such rapidity. You notice your youth fade. You see the trends emerge and dissipate, all in that desperate scramble for whatever is in fashion. You start to feel the tug of dislocation at a relatively early age. Even now, in my early forties, I can quite easily imagine a time when my cultural memories are no longer pertinent, when the songs and films that composed my life will be as alien to the mainstream as people talking about Gone With the Wind were to me when I was young.

And as that process takes place, you become increasingly reliant on the things that won't change: that were there before you and will remain there after you. The Victorian pubs, the trees on the Heath, the grand old churches and the listed buildings. They give just the right amount of rootedness in a city that will change regardless of whether you want it to or not.

The BT Tower is a reassuring reminder that some things stay the same, for a while at least. That there is solidity as well as flux, somewhere for you to find your footing. It's a reminder of the fundamental weirdness of the city, its functional eccentricity, a simultaneous look back and forward. A stamp of character, rooted right down in the drainage system and reaching up to the skies, which cannot be obliterated by passing fads. A disposition which will remain, no matter what changes around it. Even after all this time, the tower still signals the way home.

It too has been part of my life for so many years, since the early 1970s. My dad got to dine in the revolving restaurant and my Uncle worked there for a while. I remember the IRA bombs. The shock of how close they were.

Then that steamy night, when the London telephone codes changed from 01 to 071/081, I walked up Tottenham Court Road watching the light show from the tower, and tailed off into Fitzrovia to get closer. It was something like 28° at midnight that night, that seemed astonishing then (a bit too normal now).

It has been such a beacon, I still get out at Warren Street instead of Oxford St just so I can see it and walk by it. It is still the best building in London.

Oh, man… You've just made me cry.

This is so beautiful – 'Cities age you faster than towns or villages, because they shift around you with such rapidity. You notice your youth fade. You see the trends emerge and dissipate, all in that desperate scramble for whatever is in fashion.'

Kudos is due.