Brexit five years on: A triumph of lies

The promises turned out to be false. The warnings turned out to be true.

The first thing to understand about Brexit is that it is defined by lying. It was itself a lie, at its base, as a concept. It was sold through lies. It was delivered through lies. And it has now served to place the notion of lies right in the heart of our politics. It sits there - a black hole, a vortex - every day. It is the thing that cannot be named, that cannot be mentioned, the omerta. We all have to pretend it isn't there while we discuss issues like economic growth, net zero and international reputation, even though none of them can be sensibly understood without reference to it. In a way, it has turned our whole political society into a lie. It has made us fundamentally irrational.

The advocates for Leave built a vast edifice of fiction. One after another they came out during the campaign to sell people on their great idea: Michael Gove, Boris Johnson, Daniel Hannan, Nigel Farage, Dominic Cummings. Afterwards, when everything had fallen apart, they continued to thrive. Johnson made it to prime minister. Gove enjoyed a glistening ministerial career and now edits a major magazine. Farage soars in the polls even now. But the people who believed them were not so lucky. No failing upwards for them. Just the brute material reality of a country sinking under the waterline.

It fell to Theresa May to try to deliver on their promise. Her reputation has been partially resuscitated in recent years, so it is important to remember how utterly irresponsible she was in power. She didn't actually reveal anything about her Brexit policy until October 2016 - nearly four months after the referendum. She could have used that intervening time to understand the situation Britain was in by assessing the reality of European trade and law. Instead, she spent it understanding the situation her leadership was in by assessing the mood of the Tory party. That mistake would damage us all.

Instead of doing what the country needed, she said the things Tory Brexiters wanted to hear. Britain would end free movement. It would have its own trade policy. The first meant we were leaving the single market, the second that we were leaving the customs union. These were arguably the most seismic decisions taken by a British prime minister in our lifetime, but she did not seem to understand them. When she met the UK's EU ambassador Ivan Rogers afterwards, he said: "You’ve made a decision. This gives me clarity. I can work with this. We're leaving the customs union." The prime minister was baffled. "I have agreed to no such thing," she said. She literally had no idea what she was saying.

By the time May had educated herself, it was too late. She finally realised that leaving the customs union would involve putting a border in the Irish Sea and concluded, rightly, that no decent prime minister could do such a thing. Her reward for this realisation was the single biggest parliamentary rebellion against a British government in history.

It made complete sense that Johnson should emerge as her successor. The king of fabrication had come to take his rightful place in an era of political bilge. The key to the problem, he realised, was to remove any lingering sense of prime minister decency. So he simply put the border in the Irish Sea and then lied about it. It was really no more complex than that. Life is relatively simple when you give up all sense of moral endeavour.

He said there would be no border in the Irish Sea. He said businesses could put customs declaration forms "in the bin". He said he'd removed all non-tariff barriers to trade. It was all false. And we all paid the price.

His plan devastated the people unfortunate enough to be exposed to it. Goods trade was hammered. Exports to the EU by smaller businesses dropped by 30%. Around 20,000 firms ceased exporting entirely.

Services had an easier time of it. Many firms could 'mode-switch' - create a subsidiary in Europe and minimising disruption. This protected sectors like film, information services and computer programming. Financial services struggled but pulled through. Accountancy, legal and financial services were particularly hit by the end of mutual recognition of professional services.

But even in relative success stories, you saw the same picture of struggle: a reduction in efficiency, a reduction in productivity.

Sectors which had relied on free European trade now had to pivot so that their supply chain came from outside Europe. This pushed up manufacturing costs. Fewer intermediate products were imported from the EU to go into goods that the UK would trade globally, which led to a decrease in non-EU as well as EU goods trade.

Manufacturers had to take on detailed risk management and scenario planning. Many limited the products they exported, or stopping exports completely, or stockpiled components, or tried to redirect trade to new markets. In other words: they had to do more just to stay afloat. They had to swim that extra bit harder to counteract the weight that had been attached to their leg.

The really significant decline came in investment. The UK enjoyed rapid growth in business investment from 2010 to 2016. After Brexit, that stopped. It's now at roughly the same level as it was in 2016, as if we've been frozen in time. As if we've lost a decade.

Just look at this graph. It is a horror story.

Brexit removed funding from the European Investment Bank, which had always played a key role in financing infrastructure projects in the UK. It was of critical assistance in projects including the Channel Tunnel, offshore wind farms in Scotland and the Elizabeth Line. Between 2009 and 2016, its average annual lending to the UK was £6.4bn in 2024 real prices, peaking at £8bn in 2016. Then it ended. Funding fell precipitously and then simply stopped.

Just after the referendum, Brexiters made a lot out of the Treasury's wrong prediction of an immediate recession in the event of a Leave vote. In the event, the pound fell sharply, but there was no visible impact on growth. This obscured just how accurately most economists forecast what would happen after Brexit. Unlike the Treasury, they did not suggest there would be an instant explosive catastrophe. They said that we would bleed out.

The Office for Budget Responsibility concluded that "the volume of UK imports and exports will both be 15% lower in the long run than if we remained in the EU… we assume that this leads to a four per cent reduction in the potential productivity of the UK economy… with the full effect felt after 15 years." That's pretty much what happened. The OBR maintains its view on four per cent, much of which has already materialised, but some of which is still to come.

There's just one area where our worst predictions did not come true. It's about the public and the state of our political debate.

Between 2016 and 2020, we couldn't shift the dial on polling. It always hovered around the 50:50 mark. The country felt like it had been cleaved in two, as if we'd always been two nations all along. It felt like the cultural divisions in the US - guns, abortion, all these mad exotic issues - were in fact a foreshadowing of our own future mutation rather than a foreign curiosity.

The big change came in 2022, after the downfall of Johnson and Liz Truss. Suddenly polls showed a swing against Brexit, with 57% support for rejoining the EU and just 33% saying it was right to leave. Part of this was demographic churn - older Leavers dying, younger Remainers turning 18 - but some of it was a change of heart among a sizeable minority of Leave voters. Data from 2024 suggested that 23% of Leave voters would now vote to rejoin.

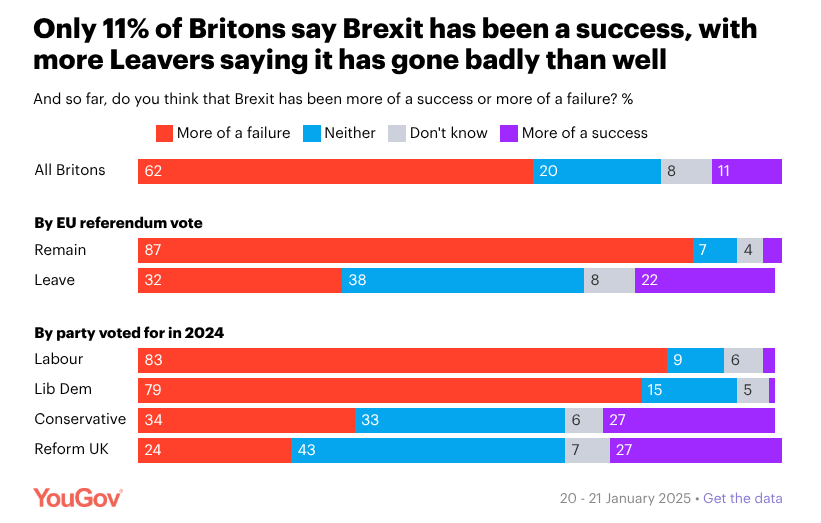

A YouGov poll this week was devastating. Just 30% now think it was right to leave the EU, compared to 55% who say it was wrong - the lowest support for the project since the firm started asking the question. Incredibly, more Leave voters think it has gone badly than well. Just look at this. It is a portrait of abject failure. It is a political corpse, in polling form.

I remember the exact moment the spell seemed to break. It was during the debate on vaccine passports. I was against them. Lots of people were for them. The issue itself didn't matter. What mattered was that, for the first time since 2016, the debate didn't seem to break down on Remain-Leave lines. It was actually quite hard to predict which way someone would go. That notion of society freezing into two warring camps began to fade. Then partygate and Liz Truss introduced a sense of universal indignation, across the political divide.

Trump liked to proudly say that he could shoot someone in public and his supporters would stick with him. But that's not the case here. This is the key positive development of our post-Brexit life. The culture war ended. We returned to something like normality.

There are many reasons to despair of what Brexit has done to us. It has reduced our sense of national pride, debilitated our economy and corrupted the sense of honesty in our national life. The greatest tragedy though, and the one people do not talk enough about, is the eradication of a particular vision of Britain: of a country that was internationalist, confident, open, liberal and moderate. A reassuring place that had found its role in the world. I don't think anyone could call us that now. We look neurotic, anxious, timid, needy and occasionally deranged.

This is one of the things the Brexit leaders will never understand: the mourning that many of us have gone through for our vision of Britain. It was nothing next to the people whose lives were upended - the Europeans in the UK, or the Brits in Europe. But we lost something intangible and yet priceless, something we might never get back: an idea of our country. And worst of all, we were told that we were unpatriotic for even loving that country, just as it was taken away from us.

So, yeah. That sucked. But despite all that, despite the horror of the last few years, there are reasons to be optimistic.

It is not glorious. It is not proud. But slowly, quietly and without fuss, we are drifting back towards Europe.

Look at the state of play. Leave is having to own the consequences of Brexit. As economic effects are felt, they are blamed on the decision to leave the EU. That is something that we were not sure would happen back in 2020. Nevertheless, it has.

Labour is moving. It says all sorts of nonsense of course - its rejection of a youth mobility scheme is particularly risible. But the basic direction is clear. Rishi Sunak ended the period of regulatory divergence. Labour has gone a step further and adopted a policy of alignment, not least through the product regulation and metrology bill. It is now pretty clear that the UK will aim to stick with what the EU is doing across different sectors.

Keir Starmer was never going to lead us back into the EU. He never claimed he would be. But after the despair of 2020, things are proceeding according to the best realistic timetable we could imagine at the time.

We don't know what'll happen next. We don't even know if we'd want to return, given the growing strength of the far right on the continent. We don't know how hard it would be to negotiate. But you'd be a fool to rule out Rejoin from where we are now. More and more, it seems like a realistic prospect in the next ten years.

Brexit is a failure. But things that once seemed impossible feel viable once more. What happens next is up to us.

Odds and Sods

All of the economic data in this newsletter came from UK in a Changing Europe's Brexit Files, released this week. You can read it here. It's a collection of essays covering almost every aspect of Brexit by some of Britain's leading academics. And, as ever with that organisation, it is pithily written, easy to read, and authoritative.

No other organisation that I know of straddles the worlds of expertise and journalism so well. They make sure the highest quality research is available to journalists in a way that they are likely to actually read and take on board. It's a kind of magic, a specific combination of attitude and approach. If it hadn't been around over these last few years, the state of the national debate would have been infinitely worse.

In the UK you have this incredible blessing of 5 year terms and very few veto points for the minority to use in the system to block things

LBJ ended segregation, passed 3 civil rights acts and the voting rights act (over filibusters) created Medicare and Medicaid and enacted The Great Society in 5 years (and still had time for a disastrous war)

Attlee nationalised coal, created the NHS, created NATO (with help but it was a UK idea) and formed an Economic system that lasted 30 years, he did all this while recovering from WW2 and in 5 years

Keating created superannuation, put in place enterprise bargaining, created the ACCC as part of broader competition policy and formed APEC all in 5 years as PM

But from Day 1 Starmer has acted like reelection is the most important thing. Why not just forget the polls, ignore the right wing papers, and just do things, use his 5 years to change the country, join the customs union, concrete over the green belt between Oxford and Cambridge fill it with houses and data centres, or don’t do any of that, just do things he wants to do, but do it, forget reelection, just change the country and who knows in 5 years the public might even reward you with reelection anyway

On the plus side, it took Brexit for me to discover Ian Dunt. Shame about it ruining the country, but, y'know.