Guestpost: Everything you need to know about the coming trade war

Donald Trump has promised an onslaught of tariffs. Here's a breakdown of what might happen next.

This is Striking 13’s first ever guest post, from trade expert Dmitry Grozoubinski. You might know Dmitry from his Twitter persona, which involves endlessly trolling me with a really rather sophisticated line of mockery concerning comic book continuity. He also has a day job advising on trade and negotiations.

He recently published Why Politicians Lie About Trade. Unfortunately for all of us, but not for him, that book just became relevant as hell. This is not a good sign. We can all remember the last time trade policy was relevant and it was not enjoyable at all.

In a moment Dmitry will break down what Trump wants with tariffs and the likely effect of that policy on all of us. If you want more detail, I strongly recommend you get his book. I’m sorry to say that you’ll probably rely on it pretty extensively over the next four years. There’s links at the bottom to pick it up online.

The normal newsletter, by an author who deeply loves and cherishes comic book continuity, will be in your inbox Friday morning. See you then.

If I had a penny for every time I’ve woken up to find out that a large group of people in a foreign country had made a democratic decision the trade consequences of which they were now frantically googling, I would have two pennies… which isn't a lot, but it's weird that it happened twice.

With both the Brexit vote and Trump’s re-election, there is simultaneously clearly a trade angle to the campaigns, but also a fairly persuasive argument to be made that the votes cast weren’t really about trade.

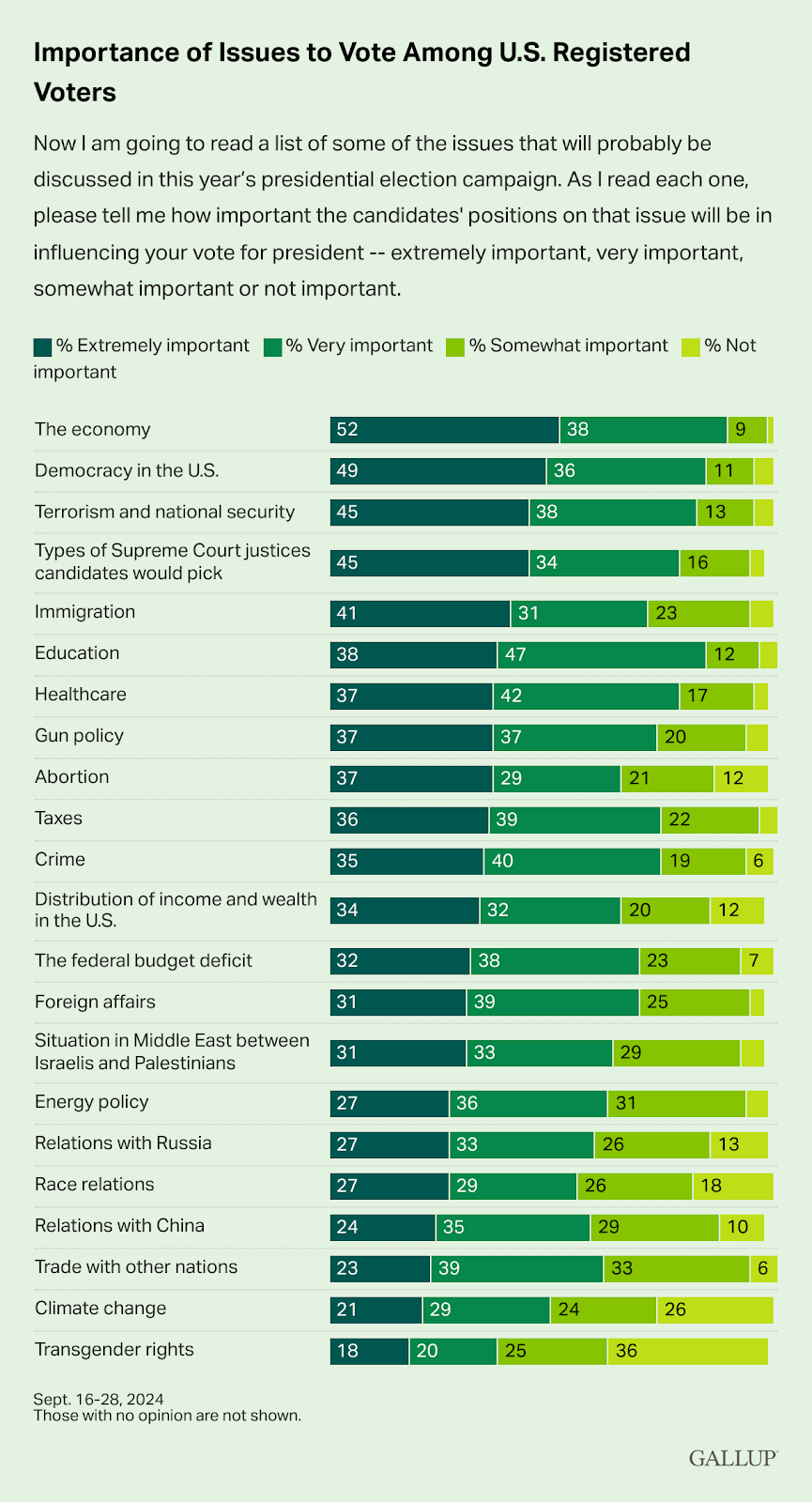

According to Gallup, trade is among the issues American voters care about the absolute least. Though trade does somehow still beat out climate change. Y… yay?

Regardless, just because trade isn’t something Americans are hugely focused on, doesn’t mean the rest of the world is immune to the trade policy choices made by the leaders they elect. And they just elected someone with some pretty strong feelings on the subject.

The Trumpian view on trade can be best described as three problems and an infatuation.

First, Trump believes that the United States has not been nearly aggressive enough in thwarting what he sees as unfair and national security compromising competition from China.

Second, Trump also believes that the United States is being taken advantage of by other countries, which sell more to the United States than they buy from it, and which he believes use tariffs of their own to keep things that way.

Third, Trump believes that American corporate, income, and payroll taxes are too high, and that there is a chance to alleviate the burden on American companies and families by reducing these – provided the revenue can be offset elsewhere.

Finally, Trump is unbelievably horny for tariffs as a concept – apparently believing them to be a victimless (domestically, at least) magic bullet solution to all three of the above problems, and sometimes seemingly every other problem he’s presented with.

I’m not here to relitigate whether this kind of thinking is wise. The American people clearly think it was, or at least don’t find it disqualifying.

What I would like to do is explain what looks set to happen next and what it might mean.

Let’s begin with some historical context.

For the last few decades, trade policy when it comes to tariffs has worked like this:

Developed countries had very low tariffs on almost everything, and had committed to one another to keep it that way under the treaties that make up the World Trade Organization, and through the Free Trade Agreements between them;

Some kept tariffs high in very specific politically or culturally sensitive sectors like certain types of agriculture;

Where tariffs were raised, it was on individual products from individual countries, either on national security grounds or as part of long and boring technical reviews by so-called anti-dumping authorities – in response to price surges or measurable unfair competition;

Debates and policy disagreements weren’t about whether to raise tariffs, but about the wisdom and conditions of further reductions through new trade agreements.

You might, if you haven’t blocked it out as a nightmarish fever dream, remember that the above was basically how the UK-US Free Trade Agreement discussion happened.

Having sworn blood oaths to unleash a tidal wave of prosperity by doing what the EU couldn’t and signing a trade deal with the United States following Brexit, successive UK administrations found their hot air balloons of enthusiasm deflated by the harpoon of reality.

One UK trade minister after another found that the US already had low tariffs, could offer precious little in terms of new access for UK services firms, and had all sorts of politically unpalatable requests of its own – from chlorine-washed chicken to greater opportunities for NHS contracting.

Yet despite how politically inconvenient it was for those Tory grandees who had vowed to rapidly deliver it, or those Leave Champions who proclaimed it as the economic prize at the end of the Brexit Rainbow, the absence of a US trade deal in 2017-2020 was not actually a major problem. At the time, a free trade agreement meant slightly widening an already open door to the US market.

This time, things are very different.

If Trump does what he has said he will do, and which he almost certainly has the legal authority to execute, the door is about to get significantly less open.

It’s hard to predict exactly what Trump’s tariffs will look like, because he has the infuriating habit of saying “yes, why not?” to literally any hypothetical posed to him, and he has at least theoretically distanced himself from Project 2025 – the closest thing we had to a detailed policy agenda for his term. But we can have a punt at it.

Let’s start with the baseline scenario – Trump levies 10%-20% tariffs on all goods, from everywhere, and 60% tariffs on all goods from China.

This means that anyone bringing commercial goods into the United States will have to pay 10%-20% of their value as a tax to Uncle Sam.

This does a couple of things pretty much automatically:

It makes foreign goods 10%-20% less competitive against American made alternatives;

It drives up prices for American consumers;

It collects some tax revenue from any foreign goods that Americans keep buying, despite these higher prices.

This is obviously bad for a British business selling goods into the US, but just how bad will vary from business to business and product to product.

Trade nerds tend to call any tariff under 5% a ‘nuisance tariff’ because the administration and logistics of calculating and paying it tend to cost more than the tariff itself. A 10% tariff is higher than that, but also not the sort of thing we consider an insurmountable wall. The UK has a 10% tariff on cars, for example, and you still see foreign autos on UK streets even from places without a UK FTA. A 20% tariff is far more significant and can be hard for any but the most competitive businesses to push through and still make sales.

The lower your competitive margins in the US market, and the more consumers who can live without your product, the more vulnerable you’ll be.

It's bad, but even a 20% tariff across the board on its own is not the nightmare scenario. After all, if it’s applied equally to everyone then British businesses would only be losing out compared to American ones – every other global competitor would be in the same boat.

The problems really begin when you think through what happens next – and what these tariffs will mean.

The US is the most lucrative market on earth. Everyone wants access to it. Everyone wants low tariff access to it. These new tariffs, and the ability to grant and remove waivers and exemptions from them, makes Trump the bouncer at the door of a club everyone is dying to get into.

Sucking up or doing a deal with Trump could mean your firms suddenly have a 10-20% edge on everyone else in the world who isn’t quite as good at toadying as you are. That can be worth billions when we’re talking about access to wealthy American consumers.

Faced with Trump’s tariffs, and their competitors around the world scheming to secure exemptions from them, countries will do one of the following three things:

Negotiate with Trump from a deliberate position of weakness, pleading the inconsequentiality of their exports to the US and hoping that a mix of investments or factory relocation to the US, personal flattery and personal diplomacy can earn them a reprieve;

Punch back with tariffs of their own on US goods, hoping that this provides enough leverage to negotiate with Trump from a position of relative strength and secure some kind of deal;

Realise they have no hope of option one and lack the strength for option two, and therefore accept the tariffs and whatever economic costs they bring.

Now it should be said that, with a good old fashioned neoliberal hat on, the above is a nightmare for investment, business growth and flexibility. Not only would the US be indiscriminately hammering its own businesses and consumers with a regressive form of taxation, but the resultant instability would make it impossible to know where to make long-term investments. It’s something the entire international trading system since 1947 was designed to avoid.

It should also be said that Trump obviously doesn’t give a damn.

Were the United Kingdom still in the European Union, it is likely that it and the bloc collectively would have adopted the second approach. While the EU is not as economically powerful as the United States, it’s still a major player and can cause a lot of pain to US firms if it chooses to. Less pain than what would flow the other way, but still a lot.

The UK does not have that kind of muscle. It may, by virtue of being smaller and thus both more agile and less threatening, pull off option one and negotiate some kind of sweetheart deal of exemption. Being outside of the European Union, the UK may also have more flexibility to make all sorts of concessions that the full bloc might shy away from. These could include:

voluntary export restrictions – the US might demand that the UK government only allow a fixed volume of exports to the US every year in certain products to push the trade balance in the US’ favour;

divestment from China – the UK isn’t as invested in China as say, Germany, and could more readily agree to limit economic engagement in a way that would please the White House;

import targets – in theory, the US could demand trading partners like the UK set and meet a target value of imports from the US annually, though exactly how a free market capitalist country like Britain is supposed to make its firms buy American against their will is an open question.

I would love to say that international relations and trade policy is a morality play or high school movie where the kind of bullying and protectionist racket the Trump administration looks poised for will inevitably lead to their getting their just desserts. I would also love to say I envision a future where the whole world bands together to collectively reject it, holding firm in solidarity. Neither is likely.

The US is large and powerful enough that, at least in the short term to medium term, it can do this and almost certainly get away with it. Governments, including I suspect the UK, will come begging at the feet of the Trump throne for a reprieve – if for no other reason than they know their competitors are doing the same.

Unlike in 2017-20, where failing to secure a trade deal with Trump meant egg on the face of some BBC Question Time regulars and little else, during this administration the UK’s trade diplomats will be negotiating for very high stakes indeed – against someone who does actually hold all the cards, and who is more than happy to throw away the rulebook.

Economics and common sense tells us that taxing imports will drive up prices for US consumers, decrease the global competitiveness of US firms by denying them the best value inputs, and lead to a tidal wave of lobbying, nepotism and corruption as businesses toady up to Trump for waivers, exemptions or additional protection. There is a price to pay for stupid policies. Unfortunately, it looks like there may be a lot of pain to be inflicted on the global economy before that price becomes so self-evident that even the new President can’t ignore it.

Click here to buy Why Politicians Lie About Trade: ... and What You Need to Know About It.

Sincerely hope Labour stay firm and do not allow the NHS to become a bargaining chip that gets tossed Trump's way. It would be the end of the NHS, and Labour.

This is a good outline, but I think it would benefit from two additions, on intermediate inputs (very briefly mentioned at the end) and on linkage with other policy areas.

To take the last one first, Vance has said the US could withhold support from NATO if the EU (continues to) regulate X (Twitter). It’s very conceivable that security assistance will be linked to trade policy in a similar way, further raising the stakes of an option 2-approach.

As for intermediate inputs, remember the Mini’s steering assembly crossing the Channel a dozen or so times during production? Lots of businesses don’t sell finished consumer products, but rather parts and widgets which are then used by US manufacturers. Those supply chains will become far more uncertain, not to mention costly, when those US manufacturers have to factor in some suppliers securing waivers or pay prices inflated by tariffs. Let alone if the supply chain includes China as well as other nations.

Say a UK company buys inputs in China, adds value in UK (or elsewhere) and then sells on to a US manufacturer, will the China-tariff apply? What if some of the links in the chain enjoy waivers but others don’t? This is a recipe for total chaos, manifest corruption and endless litigation.

And indeed, Trump doesn’t give a damn.