You don't want to read this

And I don't want to write it.

You don't want to read this and I don't want to write it. None of us wants to talk about it. We want to pretend that it didn't happen, or, failing that, to turn it into some kind of dinner party anecdote. And we’ll lean back and we’ll laugh and no-one will mention the bleakness and the horror and then we’ll hope that we can talk about something else.

But covid did happen, no matter how much we now try to brush it aside. It did take place. It forever altered our lives. And that alteration does not evaporate simply by virtue of being ignored.

It happened five years ago. We haven't settled on a day to commemorate it, but I suppose people will pick the announcement of a nationwide lockdown on March 23rd. I always think of this earlier period leading up to it, when you could see the wave of death approaching, and it became increasingly clear the political class did not have the intellectual ability to deal with it.

The first thing we did after the pandemic was to wipe covid from our cultural memory. Actually this began before it even ended. We erased it as it took place. You'd sometimes see signs of it on TV shows - someone in a face mask, perhaps, or maintaining social distance. At the time I felt a visceral desire for that to stop. It felt like an invasion. It wasn't enough for it to take my social life, now it had to take my cultural life too. Evidently everyone else felt the same way, because that shit went away pretty fucking quickly. Those early experiments in acknowledging the reality of it were quickly swept aside. In fictional universes, covid never took place.

Now we only really address covid through sublimated cultural processing. Why is there a sudden burst of David Cronenberg inspired body horror, for instance? Why are films like The Substance doing so well? Surely at least partly as a result of that covid sense memory.

I used to wonder why we never saw much about the Spanish Flu. The First World War dominates the culture of the time. It echoes down to us in poetry, literature and film. The flu pandemic which followed infected a third of the global population and killed anywhere up to 100 million people and yet you never really see anything about it. It never comes up. Apart from one informational film, which survives in the BFI National Archive, the 1918/19 pandemic doesn't appear in British film at all.

The people of 1919 blocked out the Spanish flu just like we’re blocking out covid. Too painful? That can't be it. Wars are painful and no-one feels the need to block them out. But then, wars have a narrative. They have comrades and enemies. They have tragedy and perhaps even glory. The trouble with pandemics is that they're so meaningless. They have no storyline. They have no three-act structure. We are deprived of agency. Instead we have to sit there and hope it doesn't happen to us. Then if it does happen to us, we have to lie there and hope it doesn't worsen. It is an exercise in powerlessness and passivity.

We block it out culturally because we've largely blocked it out personally. We find it increasingly hard to remember events from that period, simply because there was no content. It was a cycle of nothing, from which no memory could ever emerge. You sat in the same place, morning after morning, and did your work. Then you walked over to the same living room, evening after evening, to watch TV. In my case, that was the same room, so I had to start drinking heavily simply as a way of separating daytime from nighttime.

Most of my memories are based on discovering previously undreamed of approaches to alcohol. I remember the day I realised I might as well use 50/50 prosecco and lemonade in the Pimms. At the time, in a state of wild hysteria, I thought this might be one of the finest discoveries in the Western canon. I remember going to the bins with a wine bottle between each finger, like some kind of Rhone Valley Freddy Krueger, feeling slightly bashful when I saw the neighbour, but clocking the same deadened expression of understanding in his eye. These are not memories really. They are just straggled bits of clarity from a pit of incognisance.

Politically, we also behave as if covid never happened. The government has been building up to a green paper on sickness and disability benefits next week - a desperate attempt to hammer down soaring payments and, just as importantly, prevent further rises. In 2019, the year before the pandemic, one in 13 people between 16 and 64-years-old claimed disability or incapacity benefits. That figure is now one in ten. The bill came to £48 billion in 2023-24 and will hit almost £76bn by 2030.

Perhaps this is because the system has failed people, or because people are finding ways to cheat. It’s possible. But the soaring costs of these payments may also simply be the result of the trauma people experienced during covid. More than half the rise in disability benefit claims since the pandemic relate to mental health or behavioural conditions. Working age mortality rates have remained consistently above their pre-pandemic level. In 2023, the mortality rate was 5.5% above the 2015-19 average. Most of these were so-called 'deaths of despair' involving alcohol, suicide or drugs.

The data here is inconclusive - the increase in reported mental health conditions started pre-pandemic. But it's striking that the benefits debate takes place without any real acknowledgement of covid and what it did to our mental health.

We all know people who closed down during the pandemic and never quite came back out again. Introvert teenagers who missed this crucial period of socialisation and seemed to retreat into themselves. Older people who lost the confidence to leave the home even once it became safe to do so. Those who had minor anxiety and were then forced to spend years alone in their tiny flat, deprived of their support network. It's hardly surprising that we might see the effects of that in the benefits system.

The central experience of covid is one of loss. This ranged from the greatest loss imaginable - your partner, your parent, your grandparent - to tiny little scraps of it. Our lives were so defined by loss that we experienced it in all its forms and variations.

I noticed immediately how much I missed eye contact. On Zoom, people's eyes were never quite in the right place, they were just slightly off by virtue of the camera, so that they were in fact watching you rather than looking at you. It was an unusual sense of being disconnected from other people, in a small but crucial way, just when we most needed to be close to them. It was a cruel little distance.

I missed shaking people’s hands when we met. Shaking their hand and looking them in the eye. I missed it more than I would ever have expected. It's a nice thing, shaking hands - an expression of goodwill and openness to cooperation. The worst insult you can give it to refuse to shake an outstretched hand. The removal of it made us much more remote from humanity as a concept, from society as a group. Wherever it went, covid sliced the connections between people, in small and profound ways.

I promised myself when it was happening that I would never take these things for granted. I would never shake a man's hand like it was nothing, I would never embrace a friend without remembering what a privilege it was. But of course I do take these things for granted. Those promises never last.

We all lost really big substantial sections of our life. A couple years of life, surgically excised, the remainder stitched neatly together as if nothing ever happened. And what would have happened in those years? Which careers never took off because of the loss of that chance meeting at a conference? Which romantic relationships never happened because of the loss of that drunken encounter in a nightclub? Which children were never born because of the loss of that appointment at an IVF clinic? Which young adult, out there right now, was never able to become their best self, because of the loss of those summer days with their friends where they learned to come out of their shell?

There were gains, but even these, in the end, turned to loss.

Covid provided a form of solidarity which had been absent from Britain for nearly half a decade. Since the Brexit vote, we'd been tearing ourselves apart. People were divided against each other on the basis of really core values, in a way that seemed much more all-encompassing than the old divisions of left and right. We were at each other's throats for years. And then, suddenly, we were all in it together. You got the sense that there'd been this pent-up yearning for solidarity which had now found a way to be released.

In the initial weeks, we would go outside and bang our pots and pans, ostensibly in support for frontline workers. But I have to be honest. I never really felt the banging was about them. That was part of it, sure, but the main sentiment was a reaching out, to all the people we could no longer see on the streets, or pass in the bus, or nod to at the school gates. It said: We're still here. We're all still here. We're going through this.

Over the following months, people would be forced to make terrible decisions in the name of that social solidarity. This is what happened. This is the choice that was forced upon them. Their parents or grandparents would get covid. And their personal needs, their personal morality, would demand that they be with them. To care for them, to embrace them one last time, to hold their hand as they passed. But their social needs, their social morality, demanded that they stay away. That they keep their distance, to protect society as a whole.

We don't usually see the tension between personal and social responsibility in such stark terms. But that is what happened to them. Those were the sacrifices people made for the society they lived in.

When partygate broke, those sacrifices were made to look ridiculous. No, that's not quite right. They were made to look naive. They had presumed that we were all doing this for each other, and that others, including those in power, were behaving in the same way. After all, even the Queen had been pictured alone, without anyone to comfort her, at her husband's funeral.

When it transpired that this was not the case and that in fact Downing Street had been full of people in close contact so they could get pissed, something broke. It was that sense of social responsibility, the kind that only holds if you believe others are doing their bit. If not, you're just a mug. You're a chump. You got hustled.

This was the biggest societal loss of that period: the loss of our newfound social solidarity. It was a fragile thing, easily broken, and Boris Johnson smashed it to pieces. We don't know what that cost us yet. One day soon - the next time we need people to act for their society rather than themselves - we might find out.

But, you know, we don't want to talk about that. You don't want to read it and I don't want to write it. There's too much loss, of too many different types, experienced by too many people. It's so much easier to fixate instead on what comes next, to try to dismiss it from our memory, to turn it into a series of amusing dinner party anecdotes while the horror and anxiety fossilises inside us.

Deep down though, we know the truth. You only really start to process trauma when you stop ignoring it and begin to address it. That goes for countries as well as people.

Odds and sods

I keep meaning to include a thing about what I've been up to here but I always forget. And then sometimes I'm not really up to anything and it looks embarrassing. This is not one of those weeks though. I have both remembered and compiled things to report.

My new website went live yesterday. There's not a lot there really - I don't want to have to update it - but I needed an online basecamp which didn't look scrappy and cheap. I think it's pretty fit to be honest. I am a particularly big fan of the full stops and that thing where the copy fades into view as you scroll. The website is the work of Abi at byAbi - you should look her up if you're planning anything similar thing.

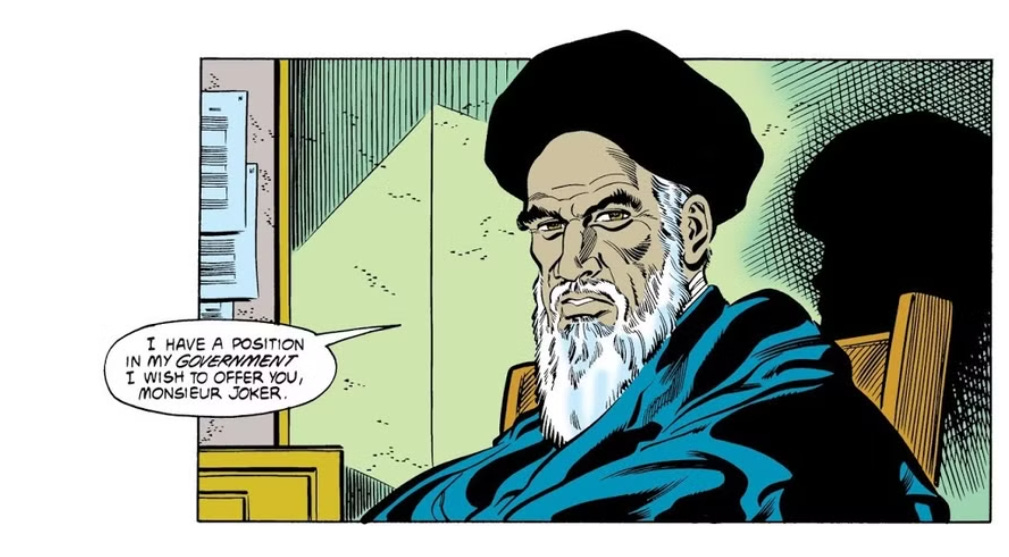

I did a Bunker podcast with Andrew Harrison on supervillain presidents in comics - a surprisingly common trope. Somewhere along the line, most of them have secured some kind of executive power, including Lex Luthor, Wilson Fisk, and Victor von Doom. We concluded that most of them were far superior to Donald Trump - morally, politically and most of all in terms of basic competence. The only caveat is Joker when he was ambassador to Iran (yes, that is a thing that really happened). He might actually have been worse. And that right there is the nicest thing I've ever said about Trump. You can listen here.

There was a Patreon-only Q&A for Origin Story this week in which we answered a bunch of questions, including why the US is particularly susceptible to conspiracy theories, what the suffix 'sceptic' really means and, most importantly, which historic event you would choose to live through if you were a rat. I would like it noted that Dorian's answer to this is possibly the worst he has ever attempted and a sure sign of his deterioration into a History TV war dad. If you're not a Patreon, you can become one here.

My piece for the i this week was about the civil war in Reform, which in no way filled me with a deep sense of delight. There is an argument there, if you look hard enough, but mostly it's just me bathing in their misfortune.

I had a great old time last night with a bottle of Zacapa 23 rum. Proper no-ice, no-mixer straight in the glass stuff. It's so warm and welcoming and fun and complicated. It's Guatemalan rum, so I'm biased. But I really do think this is as good as it gets at this price point. The XO is nicer, with a beautiful bottle, but needless to say much more expensive - I keep it for special occasions. The 23 is an excellent go-to mid-week rum.

I've been ploughing through Indian Summer: The Secret History of the End of an Empire, by Alex von Tunzelmann, on partition. It's as good a piece of popular history as I've read in years - full of characters and dynamism and accomplished storytelling, but with really mature judgement and a deep sense of empathy. A truly majestic piece of work.

Right, that's your lot. Fuck off, you lovely cunts. Have a good weekend.

This is a good piece. But I’d say it in its own way is interesting from a psychological standpoint in discussing covid as a thing that happened rather than a thing that is happening – and being routinely ignored. We still have massive covid spikes in winter. There are still people unnecessarily dying. And here in the UK, we have a government that pretends covid doesn’t exist and so doesn’t even see fit to routinely vaccinate all but the most vulnerable from a disease that is, at best, fucking horrible.

I’d managed to escape, for the most part. Then, finally, I caught covid last summer. Not sure how. Perhaps a day out at a theme park. In August. I was fortunate in that my sense of smell and taste returned almost entirely intact, but even today, I’m physically still not quite 100%. Others have it far, far worse than I do. They have been forgotten. And people are still catching covid all the time, as if that’s OK, when we have no idea what the future holds regarding its impact.

Obviously, I’m not suggesting we have some kind of permanent lockdown. But I remain absolutely stunned that people don’t mask more on public transport in winter (or by default when ill, to stop spreading their germs), and that we do not at the very least routinely and accessibly provide affordable or free covid boosters, like with flu.

But, hey, we all want to forget. Covid: past tense. Even though it’s never going away.

Thank you for writing this about COVID. As someone who was disabled by the disease, in ways that I keep discovering and no one can help with, it dizzies me how in that erasure we all did we Long COVID people were swept under the carpet. When I mention I have it, people (including myself) visibly look away and mutter and change the subject so quickly. But it's there, and the symptoms affect me every day. There are so many things I can't do anymore--and I feel fairly lucky about the things I can. I've mostly come to terms with it. And yes, when you said about shaking hands and hugging--I still tear up a bit every time I do. Somewhere deep, my soul hasn't forgotten about those years of drought. (Speaking of, it's been too long, let's arrange that dinner soooon) xx