There's an ashtray on every outside table in France, in every bistro and cafe and bar and restaurant. The ashtray stinks, of course. Years of rain have moulded with left-over ash and fag butts, leaving this stale deadened smokey tang to it. And yet it is an object of beauty nonetheless.

Over the last couple weeks, as I sat at various outside tables in Bordeaux, I found myself gazing at those ashtrays. I don't smoke anymore, but it doesn't matter. I love what they represent. They say: Yes. You can. As a point of general principle. And that is a message that goes well beyond smoking, to the heart of what a society is all about.

We like to praise ourselves for our sense of freedom in Britain. "The liberty of the individual is still believed in, almost as in the nineteenth century," George Orwell once wrote. "It is the liberty to have a home of your own, to do what you like in your spare time, to choose your own amusements instead of having them chosen for you from above. The most hateful of all names in an English ear is Nosey Parker." Maybe this was once true but it's certainly not true anymore. Britain labours under an extraordinary number of rules. These include legislation, obviously, and the whole shadowy area of tertiary law where guidance is turned into mandatory command. But in your day-to-day life, it is more commonly represented by a sub-category of officialdom operating at the high street level.

Go out for an evening and keep track of how many people tell you what to do. If you have your child with you, you will often be told to leave a pub at a certain time. I've seen this done with a stone face and a judgemental glare by bouncer type figures, as if the mother was clearly a moral failure simply for enjoying a glass of wine with a child beside her. You will certainly be told where you can and can't smoke, or vape. You won't be allowed to do either inside, but as you leave to go outside you will be told that you cannot take your drink with you. If you start to have a good time outside, you will soon be told to go inside, because of supposed noise concerns from local residents. And then, when it gets to just 11pm, you will be told to go home, or - laughably once you've reached your 40s - to go find a nightclub somewhere to continue your conversation.

Nightlife in Britain is increasingly an exercise in control and submission. The core lesson you learn is about priorities. Enjoyment is not the priority. Socialising is not the priority. Certainly joy or freedom are not the priorities. The priority is noise reduction, the concerns of local residents, careful obedience to the minutiae of public health laws, and strict adherence to the full panoply of local and national rules.

In France, there is a very different set of priorities. It's not like they are great lovers of liberty either. Whenever you have to do something official, like rent a home, or hire an employee, or even join a gym, officialdom comes swaggering into view with immense demands. The country's labour code governing work regulations ran to 3,448 pages by 2017 – much longer than the Bible. The hairdressing code alone has 304 pages. When the umbrella-maker Pierre de Jean was asked by a journalist how he managed to keep manufacturing in France, he replied in a magnificently French way. "Through taste," he said, "and folly."

But the French believe in socialising, almost as a national religion. They believe in the great things that can happen in the nighttime when friends gather to chat. They believe in good wine and decent conversation. That's why that ashtray is there and it is what it represents. Yes, you can. Society is geared up for those who want to do, not those who want to stop them. It is possible to feel truly free at those moments in a way that is increasingly impossible in Britain. Yes, take your glass outside. Yes, stay out late. Yes, have a cigarette. And no: you cannot stop other people doing these things simply because you happen to find it unwise or inconvenient.

Barring a change of position, it now seems pretty clear that Labour will try to ban smoking outside pubs and restaurants, including on pavements.

There are all sorts of practical and political reasons for why this is unwise. The first is the state of the pub industry. They have been battered, initially by covid and then the cost of living crisis. They're getting absolutely hammered out there. The government seems to have developed this idea without even bothering to check beforehand what the implications might be.

Nor is the move even sensible politically. Labour will be confident in the lack of opposition. The Tories have no right to talk about it given they just supported a draconian attempt to ban smoking outright. The public support the ban. They'd support any ban. It doesn't really matter what it is. They just like banning things. Never forget that during covid 19% of Brits wanted a permanent 10pm curfew even once all threat of a pandemic had disappeared. People are just basically dreadful.

The political danger is not about opposition, but priorities. Each bit of legislation takes time - to write, to test, to pass in parliament, to implement, to defend in the courts if necessary. It uses up bandwidth. We have a health disaster in this country - an NHS on its knees, waiting lists out of control, a void where GP appointments should be, long waits for specialist appointments, and no preventative aspect to the system even when things are ticking along nicely. Focusing on banning smoking outside in that context is, at best, displacement activity. It uses up the hugely valuable early days of the administration on an eye-catching but superficial initiative. This is the sort of thing governments do at the end of their lives, not the start.

But honestly those are not the main concerns. The main concerns must ultimately be philosophical.

Liberals believe the following proposition: You should be able to do what you like as long as you are not hurting someone else. It's a simple idea that most people claim to believe in and precious few actually live by.

The indoor ban was tolerable because passive smoke can harm someone's health. As it happens, this really wasn't pertinent to fellow drinkers - the people who get this are usually bar workers, who are there every single day, or, more commonly, spouses, who live with the smoker their whole lives. But there really was no way to protect the staff without having them sign a disclaimer signing away their safety rights. And if we allowed that for one sector, what's to stop it in construction and other areas? Ultimately, the indoor ban was acceptable on liberal grounds. Smoking indoors can hurt other people.

Smoking outdoors does not. There is no meaningful cancer risk from someone smoking at the next table in a pub garden. Instead, the most common refrain in these scenarios is that the smoke is unpleasant for others.

Even that states it a bit too highly. I don't smoke. The rare whiffs of a cigarette nearby are a perfectly manageable inconvenience. They're considerably less dreadful than all the other unpleasantness we must be able to tolerate if we are to live in a society together: someone with bad personal hygiene, or screaming toddlers, or, worst of all, teenagers applying so much Hugo Boss perfume you can almost taste it when they pass you in the street.

There are many things people do that I do not like. I do not like overhearing their godawful opinions when I am trying to drink my coffee. I do not like seeing wannabe-influencers taking a thousand photos of themselves. I do not like hearing businessmen talk self-importantly on the phone, their voices raised specifically to project a sense of their professional status, and also presumably to mask their long history of sexual failure. But we do not ban things to prevent inconvenience, or distaste. We ban only to prevent harm. Let's say that word again, because it is important. Harm. That is a high bar. It does not cover inconvenience and no civilised person with a responsible sense of societal health would presume otherwise.

We are creating a country without the capacity for fun. One which is so tightly regulated and so suffocatingly controlled that you can almost see the whimsy asphyxiate right there in front of you. One where joy and laughter in the evening is regulated to within an inch of its life. We are giving this country wholesale to Orwell's nosey-parker. To the curtain-twitcher. To the prurient, the hectoring and the puritanical.

There is a very profound philosophical principle that they should try their best to comprehend: Mind your own fucking business. Unfortunately, it’s one the government seems completely oblivious to.

Odds and sods

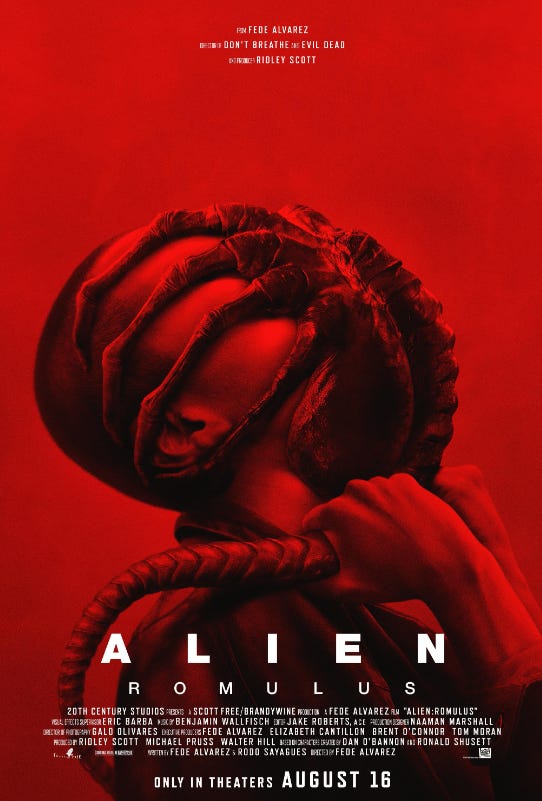

I saw Alien Romulus recently and it absolutely did my head in. No clear spoilers below but there's a few vague references to events.

I don't remember the first time I watched Alien, but I remember the feelings it gave me. First, violation. Second, visceral disgust. Third, the deep and abiding sense that corporations do not want what's best for you. And fourth, a lesson in hubris. These were the seminal life instructions given to me by science fiction.

Many of my more utopian friends received similar moral guidance from Star Trek. There, mankind is progressive, rational, adventurous, and destined for great things. That was not my kind of sci-fi. I tried watching it several times and thought: When do these cunts get fucked up? I preferred the idea of fear and disgust, the notion that far out there, in the depths of space, there are things that are squishy and gloopy and parasitic and that they will nest in your intestines and turn you into pulverised meat.

I think those first feelings about Alien reflect its most basic components, the core mechanics of the thing - the reason it works. Its first element is that sense of violation. It's one of the very few horror films that plays on straight male fears rather than simply female ones. Most horror movies feature a female character trying to escape a male killer - whether he's human (Halloween), undead (A Nightmare on Elm Street), Satan (Rosemary's Baby, The Exorcist), or her husband (The Shining). Alien, on the other hand, had a strangely ambivalent view of gender. Ripley was originally supposed to be a man and all the characters are written in such a way that they could be male or female. The fear it stimulates is pretty clearly that of rape, but even here it's not a specifically female fear of the crime but perhaps more a male one - of penetration, impregnation. The whole thing is a media studies festival in film form. Abstract enough to trigger all these interpretations and specific enough to give them purchase.

The second element is the fear of the unknown. I've always been a squeamish little coward. If I saw a slug when I was a kid I'd run away screaming. I'm honestly not much improved as an adult. I'm a proper city boy. I have a deep disgust for the gooeyness of nature, the gunky, slimy, decaying unknowableness of it. Alien plugs right into that primordial fear. The flash of teeth in the nighttime, the reflection of eyes in the jungle. The Alien was not going to fuck you up out of animosity, but in an entirely amoral way, by virtue of its natural lifecycle. It was therefore far more terrifying than the Predator, specifically because it was so incomprehensible. It didn't seek triumph or glory or even victory. It was just doing its thing. It looked at us the way a human looks at a goose it wants to use for foie gras.

The third is a suspicion of capitalism and in particular a paranoia about large corporations. Alien is working class sci-fi. Unlike in later Ridley Scott films, the characters do not talk about the origin of life. They talk about their contractual obligations and the amount they are getting paid. The corporation they work for - Weyland Yutani - lies to them. It treats them as worthless flesh units which can be sacrificed to achieve its goals. The set is full of hallways, oil, steam and industry - ingeniously designed to mimic the organic form of the Alien, as if the corporation's space ships are just as unknowable and dangerous as the specimens they find.

The fourth is a parable about hubris. At some point, all good Alien stories boil down to a kind of Greek myth, or a parable, about humankind's hubris. It's about what happens when you try to tame nature, or profit from it, when you take that which is chaotic and attempt to make it orderly.

It's very fashionable to slag off franchises as unoriginal and unimaginative. It's always been fashionable. In the 90s, people said the same thing about sequels. People seem to think that every work of art should be utterly new. But some ideas, or bundles of ideas, are so good that they can go on indefinitely. Doctor Who. Superhero universes. Mission Impossible. Laurel and Hardy. Even genres are basically a version of this. A rom-com is a bundle of tropes, plots and ideas. They're good enough that you can keep on doing it.

All of which is to say that I was full of excitement when I went to go see Alien Romulus. And that I was full of disappointment by the time it was over.

There's some good nasty crunchy horror in there. There were two things I hadn't seen before in an Alien film and one I hadn't seen anywhere - not a bad hit rate. It's certainly better than anything since Alien 3, although that is a bar so low you can hurdle it by shuffling. But it made two really big mistakes.

The first was to try and bring in Prometheus lore. That's just a straight-up error. That stuff must die. No-one likes it. No-one wanted more of it. Just let it perish.

The second is more pernicious: the preference for nostalgia over daring. And that is not a product of people who really love the original films. It is the product of people who have insufficient faith in them.

Take Prey, the Predator update from 2022. Predator is a far worse idea than Alien: an extraterrestrial hunter who comes to earth as a kind of safari. It doesn't lend itself to metaphor as Alien does. Prey could have ramped up the bombastic 80s action music from the original, had the characters shout Arnie's lines ("You're one ugly motherfucker") and pissed about in left-over bits of continuity. But instead it did something much more adventurous. It had enough confidence in Predator's core concept to transpose it to a completely different place and time - the Northern Plains in the 18th Century - with a completely different set of characters. It maintained the crucial elements, but jettisoned the nostalgia. It really believed in Predator and could therefore take it to exciting new areas.

We saw the same thing happen with Star Wars. The Last Jedi dared to branch out in new directions. The core bundle of traits were there, but it wanted to say something new, to break down the simple binary of the light and dark side of the force, to challenge the bloodline element. And then of course the fans got upset and they jettisoned everything interesting in the next film. Instead, we got all the Star Wars hits. Emperor Palpatine is back, for no reason whatsoever and without explanation. The bloodline element is restored. The same old song plays over and over again.

This is the nostalgia machine. We see it very often now. We do not really get a new film in a series. We get a greatest hits parade. That's what we ended up with in Romulus. A character from the past returns, pointlessly. Another character says one of Sigourney Weaver's old lines from Aliens (“Get away from her you bitch”). Step by step, we recreate the things that thrilled us in the past, and by doing so tacitly accept that we have no fresh things to thrill us in the present.

Alien's core bundle of ideas and concept is strong enough to warrant completely different storytelling, in completely different settings: modern day earth, old wooden planets, religious communities in the jungle, the mediaeval period. All the best Alien comics and novels have done this. But to do that, you need real confidence in the source material.

Fuck reverence. Fuck homage. It’ll kill the things you love.

I was waiting for a concert to start the other day. It was a stadium gig, so outdoors, and I had gotten there early as I wanted a good spot. But a pretty tight spot, and next to me there was a group of 6 people who never stopped smoking the entire time, and this is probably for a good 7 hours. By the end of the night I left feeling nauceous and with a smoker's cough. So yes, smoking outdoors can absolutely do someone else harm, and these people couldn't even be bothered to blow the smoke in a different direction when I asked them to. So I am all for banning it in certain places. It's nasty, and not at all the same as having to listen to a conversation you don't like.

As a long term sufferer of allergic rhinitis, I entirely disagree with your suggestion that an ash tray on a table represents freedom, and I entirely disagree with your suggestion that smoking outside is harmless to the people nearby.

On those points you are simply wrong.

You do have a point that there are better priorities for the limited time for legislation, but please discard the myth that smoking is only a threat to other people in enclosed spaces